Website redesign in a maternity setting: Co-designing a resource for consumer support and education

Taryn Elder1, Leanne Cummins1, Claudia Tait1, Wendy Kuzela1

Abstract

Women want to be informed about their healthcare. Google searches

provide an accessible option for women during pregnancy, but the

content is largely unmonitored. Women have expressed dissatisfaction and

confusion about receiving conflicting information from clinicians across

the maternity service. It is essential for providers to offer

person-centred care and listen to the voices of consumers. If the aim

is to provide a service women want to use, women must have the

opportunity to voice what they want. The local health district (LHD)

maternity website development project aimed to redesign maternity

website pages over 12 months to meet community needs and increase hits

to the site by 70% within six months. Consumers were approached to

participate through maternity services in a regional Australian health

district where approximately 3,500 babies are born yearly. In a

three-phase participatory action research study, researchers identified

the areas of concern for consumers, worked with them to co-design and

implement a new website, and evaluated the changes. Almost 20% of women

who birthed from January to March 2022 responded to the evaluation

survey. Half of these had explored the website. After the upgrades, the

number of hits to the district website service page increased by 875

(from 124 to 999). Post-development surveys showed that women who felt

they received inconsistent information at the hospital during their

pregnancy were more likely to visit the website for clarification (p =

0.009). Of women who visited the website, 78% found the information

useful, and 73% said they would use it again. This study highlighted

that women engaging in maternity services desire access to relevant,

quality information through digital technology. Maternity website

development improvements increased patient satisfaction and reduced

confusion, providing a reliable source of accessible health information

for consumers.

Keywords:maternity, digital, website, education, antenatal

1Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District

Corresponding author:Mrs Taryn J Elder, Shoalhaven

District Memorial Hospital, Nowra NSW 2540,

[email protected]

Introduction

The World Health Organization recognises women's health during the

perinatal period as a foundation for population health (Nieuwenhuijze &

Leahy-Warrant 2019). This acknowledgement demonstrates the importance of

prioritising accessible, trusted information for women. Empowering women

through pregnancy and childbirth education is believed to lead to more

positive outcomes in pregnancy and birth that also continue into motherhood

(Vedam et al. 2017). Therefore, the design and implementation of good

quality, consistent education for women and their families must be a

priority of maternity service delivery. Women report greater satisfaction

with birth experiences when involved in decision-making (Vedam et al.

2017). Many pregnant women report using online media to supplement their

knowledge of pregnancy and childbirth concerns. This highlights online

media as a significant resource for maternity care providers to develop

quality antenatal education (Alainmoghaddam, Phibbs & Benn 2018). When

providers offer accessible, trusted information, women can change from

passive recipients into collaborative partners in the healthcare space

(Vedam et al. 2017). The significant barriers women report include needing

more information, lack of access and receiving conflicting or inconsistent

information (Alainmoghaddam, Phibbs & Benn 2018, Cummins, Wilson &

Meedya 2022). These barriers can be remedied by providing an improved,

trusted, accessible one-stop information source for women via a digital

platform (Alainmoghaddam, Phibbs & Benn 2018, Cummins, Wilson &

Meedya 2022).

This paper outlines the considerations in designing a maternity website,

including acknowledging the diverse community within the Illawarra

Shoalhaven Local Health District (ISLHD). In this region, 3.4% of people

identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander (compared to 2.4% in

NSW), 9% were born in a predominantly non-English speaking country, 26%

lived in the most disadvantaged communities in the region (compared to 20%

in NSW) and there was a growing number of refugees (Illawarra Shoalhaven

Local Health District 2019). Three models of maternity care are used in the

ISLHD: doctors' clinics, antenatal general practitioner shared care and

midwifery-led clinics (Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District 2019).

Methods

Participatory action research (PAR) methodology was chosen for this study,

as the team wanted to work with consumers to gain their insights into how

they thought healthcare information could be improved for all users of the

maternity services website. Phase 1 identified areas of concern, and Phase

2 involved working with consumers, staff and LHD stakeholders to co-design

and implement an improved website. Phase 3 evaluated whether consumers were

using the website, were satisfied with the changes and would use the

website again.

Ethics approval to conduct this research was granted by the ISLHD Low and

Negligible Risk Research Review Committee (ISLHD/QA147). All participants

were provided with project information and gave their consent to

participate. Responses received were anonymous.

PHASE 1: IDENTIFICATION OF CONSUMER CONCERNS

Phase 1 sampled 60 women receiving maternity care through Wollongong

hospital via a convenient online Qualtrics survey. Staff asked participants

to fill in a survey that asked whether they knew a website existed, whether

they had used it and what they looked for. If they had not yet seen the

site, consumers were given the website link to evaluate it at that time and

answer further questions. They were then asked what they would like to see

on an improved hospital-based maternity website to enhance the information

gathered from stakeholders in Phase 2 focus groups. Surveys were anonymous

and could be completed in paper form while women waited in the antenatal

clinic or online via Qualtrics. Consent was implied with completion. All

paper-based forms were entered into Qualtrics and then destroyed. Online

survey answers were kept on a password-protected computer.

PHASE 2: CO-DESIGNING AN INTERVENTION

In 2020, ISLHD had a basic website that included service information. The

study identified what stakeholders thought should be changed on the website

through focus groups of maternity consumers, staff and health support

services, such as multicultural and Aboriginal health services.

Participants were sought through community consumer groups, and staff from

all areas of maternity and health support services were invited to attend.

Three focus groups of four to 10 participants were run from February to

March 2021 to co-design ideas for a new maternity website that would serve

the needs of consumers. Facilitators informed all focus groups of the

outcomes of Phase 1 consumer surveys. Notes from focus groups were taken,

and themes were gathered from all groups. No participants were identified.

All files were confidential and kept on a password-protected computer.

Reflexive thematic analysis was conducted during the three focus groups

following Braun and Clarke's (2006, 2021) six phases of analysis.

Researchers immersed themselves in the emerging data, created themes and

revisited them until data collection was complete. There were no new ideas

after the three focus groups were completed. The co-designed ideas became

the basis for new maternity website pages, and construction started in

March 2021. Researchers worked with district leaders to ensure National

Safety and Quality Health Service Standards were met for ISLHD by

implementing a website that improved the quality of health service

provision, partnered with consumers and protected the public from harm

(Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care 2022).

Development of the new website pages concluded in September 2021, and they

were then advertised to maternity consumers via posters in antenatal

clinics, general practitioner surgeries, birthing units and maternity

wards.

PHASE 3: EVALUATION

The website team aimed to increase visits to the new maternity site.

Therefore, the number of visits and average time spent on the pages were

measured and evaluated. To determine whether consumers would revisit the

site, an invitation to participate in the Phase 3 online website evaluation

survey was sent to all women who birthed between January and March 2022 (n

= 1,060) across the district via SMS. Survey questions such as 'did you

find the website useful?' and 'would you use it again?' evaluated consumer

experiences.

Results

Results across the three phases of the study show how information was

gathered to co-design a website well utilised by consumers.

PHASE 1: IDENTIFICATION OF CONSUMER CONCERNS

The study received 60 surveys from women about the website available to

them in 2020 (Table 1). All respondents had looked for pregnancy information

online, but almost one in four did not know a maternity website existed for

the hospital, and 40% thought it was hard to find. Participants were asked

to comment on their first impression of the hospital website. Comments were

received from 32% of participants, and all of them had negative

connotations, such as 'not enough information', 'impersonal',

'disappointing', 'clunky' and 'confusing'.

Most consumer responses (80%) showed they were looking for general

information about birth, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) or midwifery

models of care. Over half of the respondents looked to the website for

general pregnancy advice. However, only 10% reported that finding the

information they sought was easy.

Table 1: Consumer survey responses to 2020 website

|

Website 2020 Consumer Responses

|

n (%)

|

|

Used websites to look for maternity information

|

60 (100)

|

|

Unaware of the hospital website

|

14 (23)

|

|

Found the hospital website hard to find

|

24 (40)

|

|

Had a negative first impression

|

19 (32)

|

|

Found it easy to find the information sought

|

6 (10)

|

|

Sought general information (Midwifery Group Practice,

gestational diabetes mellitus [GDM], birth)

|

48 (80)

|

|

Sought general pregnancy advice

|

34 (57)

|

|

Sought antenatal classes

|

23 (38)

|

|

Sought breastfeeding information

|

15 (25)

|

To inform the focus groups in the next phase of the study, we asked survey

participants what they would like changed in new website pages. Every

respondent commented. Responses ranged from suggestions about how the

website looked (e.g., add photographs, videos and tours, reduce clinical

language) to requests for more specific information on antenatal models of

care and advice around pregnancy, GDM and breastfeeding.

PHASE 2: CO-DESIGNING AN INTERVENTION

Three focus groups of consumers, staff and community stakeholders were run

in February and March 2021. Results from Phase 1 were shared to start a

conversation. Groups collaborated using mind maps. No new themes emerged

from the first focus group; however, it was important for researchers to

talk to as many staff, consumers and stakeholders as possible. During that

time, researchers spoke to 19 people with interest in improving the

hospital-based maternity website:

- Workshop 1: eight onsumers, two staff

- Workshop 2: one consumer, two ISLHD stakeholders, two staff

- Workshop 3: one stakeholder, three staff.

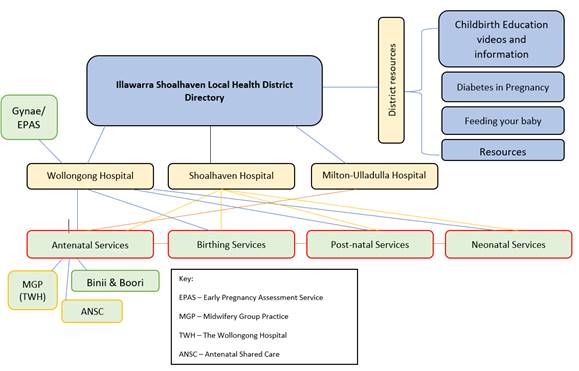

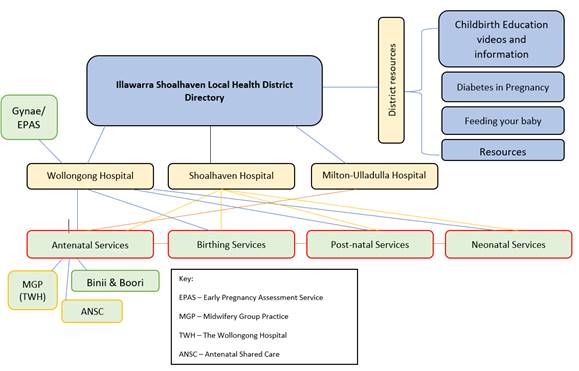

Following the collaboration, the groups designed a flowchart for a new

website to submit to the LHD's quality and safety committee for approval

before the website team began construction (Figure 1). The LHD has three

hospitals that provide antenatal services and two that offer birth services.

New pages would be required for each of these and district information pages

on topics such as childbirth education, GDM and breastfeeding.

Figure 1. Outline of flowchart for maternity web pages

Information for each page was gathered from consumer recommendations and

the clinical educators in each area. It included photographs, videos and

tours and considered the Clinical Excellence Commission's health literacy

guidelines (NSW Government Clinical Excellence Commission 2022).

PHASE 3: EVALUATION

Evaluation of the website during Phase 3 by measuring webpage use and

asking maternity service users about their experiences. In September 2020,

the website was limited to pages with information about the service (e.g.,

phone numbers) and a general description. The study measured visits to the

main district page and the average time visitors spent there.

In September 2020, the average number of visits per month in the previous

six months was 539, and the average time spent on each page ranged from 41

seconds to under three minutes (Table 2). The new pages were completed in

September 2021 and then advertised. From January to February 2022, the

monthly usage rate was 6,613 visitors across all maternity pages, and

visitors were engaged on each page for an average of one to four minutes.

Visits to all areas of maternity services were enhanced by improving the

pages and letting consumers know the site existed.

Table 2. Visits to maternity website 2020 and 2022

|

Page Title

|

Visits per Month March to September 2020

|

Average Time (minutes) 2020

|

New Pages Built

|

Visits per Month January to February 2022

|

Average Time (minutes) 2022

|

|

District services main page

|

124

|

0.41

|

District

|

999

|

1.24

|

|

Postnatal services

|

12

|

1:33

|

TWH

|

118

|

2.36

|

|

|

|

|

SDMH

|

41

|

1.21

|

|

Birthing services

|

69

|

1:53

|

TWH

|

476

|

3.43

|

|

|

|

|

SDMH

|

75

|

2.15

|

|

Antenatal services

|

120

|

2:53

|

TWH

|

592

|

3.47

|

|

|

|

|

SDMH

|

45

|

2.00

|

|

|

|

|

MUH

|

15

|

1.43

|

|

Neonatal services

|

8

|

1:55

|

TWH

|

47

|

3.06

|

|

|

|

|

SDMH

|

12

|

1.08

|

|

Feeding your baby

|

N/A

|

|

District

|

502

|

2.46

|

|

Childbirth education

|

N/A

|

|

District

|

558

|

4.08

|

|

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)

|

N/A

|

|

District

|

147

|

3.15

|

In addition to attracting more visitors to the maternity website, the

researchers also wanted to evaluate whether women found the information

useful or would use the website again. An invitation to participate in an

online survey to was sent to 1,060 women who birthed across the district

between January and March 2022, and 11.5% of those responded (n=122). Almost

half of the respondents (47.5%) had used the website (n = 58), and, of

those, 53% were having their first baby and 19% were aged 36 years or over.

Of the 122 women who responded to the survey, 41.3% (n = 50) stated they

did not feel they received consistent information while in hospital. Of

these women, 53.4% looked at the website to clarify information (p =

0.009).

Of the women who used the website (Table 3), 78.8% found it easy to use,

73% would use it again, 69.2% thought the information was well organised

and 63.5% thought the information was easy to find (63.5%). A third

accessed the website to help manage breastfeeding issues. Overall, 80.8%

were satisfied with the website pages.

Table 3. Consumer survey responses to 2022 website

|

Website 2022 Consumer Responses (n = 58)

|

n (%)

|

|

Having their first baby

|

31 (53.4)

|

|

Aged 36 years or over

|

11 (19)

|

|

Found the website easy to use

|

41 (78.8)

|

|

Found it easy to find information

|

33 (63.5)

|

|

Found the information well organised

|

36 (69.2)

|

|

Would use the website again

|

38 (73.1)

|

|

Used information for breastfeeding issues

|

16 (33)

|

|

Were satisfied with the pages

|

42 (80.8)

|

Discussion

The high percentage of responses received in the study highlighted that

women wanted to be heard, which informed the creation and management of the

website. Many women use digital technology to access health information

about their maternity care (Alainmoghaddam, Phibbs & Benn 2018). The

maternity care team should use websites and social media to capitalise on

these forms of communication as key methods of health promotion. This may

allow healthcare professionals to positively influence care and provide

women with an avenue to allay their concerns more promptly (Alainmoghaddam,

Phibbs & Benn 2018, Lupton & Maslen 2019).

After the website was developed, the statistical records showed that the

number of visits increased as more women were utilising it to gather

information. The participants felt they received conflicting information

while in hospital. This is consistent with reports from other maternity

services, specifically regarding information about breastfeeding and GDM

(Alainmoghaddam, Phibbs & Benn 2018, Cummins, Meedya & Wilson

2021). This validates the website development team's action and provides

scope for further updates and enhancements.

Providing quality education to empower women's decision-making during

pregnancy is imperative. Enhancing a maternity website in any LHD will

positively impact prenatal and postnatal health outcomes (Nieuwenhuijze

& Leahy-Warrant 2019). Further research should be undertaken amongst

different pregnancy cohorts to assess and develop the impact of online

information.

Practice implications

The results demonstrated that co-designing a website with consumers, staff

and ISLHD stakeholders enabled the website team to develop well-utilised

pages that offered consumers relevant, evidence-based information and

education. Maternity services can support consumers by providing a website

that has the information they want and need to clarify information gained

from other sources.

IDENTIFIED SERVICE GAP

From the research, the website development team was able to identify and

address a service gap. Women did not always receive consistent information

from the hospital system. The redevelopment of the website improved the

availability and accessibility of appropriate quality information.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

Identified strengths of the study were the high response rate and a

qualitative research method where women were encouraged to share their

priorities with the website development team.

There were also some limitations to this research. The target demographic

is women who can access and use digital technology via a computer or

smartphone. This may exclude some women. The research required women to

recall their previous experiences within the healthcare system. While the

period between the healthcare interaction and the research contact was not

excessive, there was potential for participant recall bias. It should also

be noted that the question in the survey asking whether participants would

use the website again provided no opportunity for a contextual response.

Therefore, this question could include responses from women who would not

use the website again due to having completed their families.

Conclusion

The study identified that women have stated that they are not receiving

consistent information from the hospital system. The researchers were able

to address this concern through the implementation of a website with

accessible, high-quality information. The website provided a trusted

information resource many women said they would use again.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the research participants who contributed to

this work. Their participation has been invaluable in helping the

researchers develop the website and complete the study.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

Alainmoghaddam, N, Phibbs, S & Benn, C 2018, '"I did a lot of

googling": A qualitative study of exclusive breastfeed support through

social media', Women and Birth, vol 32, pp. 147-156.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2018.05.008

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care 2022,

National Safety and Quality Health Service (NSQHS) Standards

.

https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/nsqhs-standards

Braun, V & Clarke, V 2021, 'One size fits all? What counts as quality

practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis?',

Qualitative Research in Psychology

, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 328-352.

Braun, V & Clarke, V 2006, 'Using thematic analysis in psychology',

Qualitative Research in Psychology

, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 77-101.

https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Cummins, L, Meedya, S & Wilson, V 2021, 'Factors that positively

influence in-hospital exclusive breastfeeding among women with gestational

diabetes: An integrative review',

Women and Birth: Journal of the Australian College of Midwives

, vol. 35, mo. 1, pp. 3-10.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2021.03.005

Cummins, L., Wilson, V & Meedya, S 2022, 'What do women with

gestational diabetes want for breastfeeding support? A participatory action

research study', Breastfeeding Review,vol. 30, no. 3, pp.

27-36.

"What do women with gestational diabetes want for breastfeeding

support" by Leanne Cummins, Valerie Wilson et al. (uow.edu.au)

Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District 2019,

It's your health that matters - Health Care Services Plan 2020-2030

, p. 49.

https://www.islhd.health.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/Health

Plans/Final Health Care Services Plan 2020-2030.pdf

Lupton, D & Maslen, S 2019, 'How women use digital technologies for

Health: Qualitative interview and focus group study',

Journal of Medical Internet Research,

vol. 21, no. 1.

Journal of Medical Internet Research - How Women Use Digital

Technologies for Health: Qualitative Interview and Focus Group Study

(jmir.org)

Nieuwenhuijze, M & Leahy-Warrant, P 2019, 'Women's empowerment in

pregnancy and childbirth: A concept analysis', Midwifery, vol. 78,

pp. 1-7.

Women's empowerment in pregnancy and childbirth: A concept analysis -

ScienceDirect

NSW Government Clinical Excellence Commission 2022,

Health Literacy

.

Health literacy - Clinical Excellence Commission (nsw.gov.au)

Vedam, S, Stoll, K, Martin, K, Rubashkin, N, Patridge, S, Thordason, D

& Jolicoeur G 2017. 'The mother's autonomy in decision making (MADM)

scale: Patient led development of psychometric testing of a new instrument

to evaluate experience of maternity care', PLOS One, vol. 12, no.

2.

The Mother's Autonomy in Decision Making (MADM) scale: Patient-led

development and psychometric testing of a new instrument to evaluate

experience of maternity care - PubMed (nih.gov)